von Martina Sander

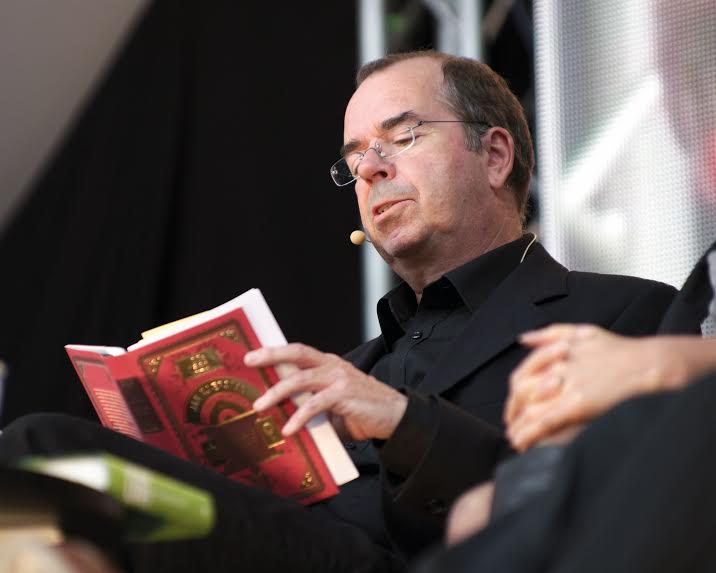

Jan Kjaerstad gilt als einer der bedeutendsten Schriftsteller der Gegenwart. 1953 in Oslo geboren, war der Norweger zuerst Pastor, Jazzpianist und Redakteur der Literaturzeitschrift „Vinduet“. Zurecht gewann er 2001 die wichtigste literarische Auszeichnung Skandinaviens, den “Literaturpreis des Nordischen Rates”. Sein Werk umfasst neben seinem stattlichen Romanwerk auch Essays, Kurzgeschichten, Artikel sowie Bilder- und Kinderbücher.

Kjærstads Romane sind von epischen Ausmaßen, angereichert durch ein enzyklopädisches Wissen, das er ohne Rücksicht auf den Leser/die Leserin ausschüttet, als hätte er einen umfassenden Bildungsauftrag. Seine Bücher sind brillant. Sie sind sehr gut konstruiert, witzig, subtil, haben einen schlüssigen Plot, verlangen dem Leser/der Leserin aber einiges ab. Sein Stil ist manchmal fast manisch überhastet, er springt zwischen den Zeitebenen hin und her, lässt sehr viele Figuren sich in seinem Universum verlieren. Wollte man jedem Zitat, jedem Autor, jedem Musikhinweis nachgehen, Kjaerstads Lebenswerk würde zum eigenen. Andererseits sind seine Romane hypermodern und nehmen aktuelle Fragen auf und sparen nicht mit Gesellschaftskritik. Seine skurrilen Charaktere sind so wundervolle Verlierer, moderne Don Quijotes, jeder mit einem Alleinstellungsmerkmal, die einen eigenen Roman wert wären.

Im Interview hat uns der Autor Rede und Antwort gestanden und ein bisschen Licht in sein Universum gebracht.

Your book “Kongen av Europa” has just come out in Germany. How does that feel?

It feels great. But that sounds too weak. I’ll rather say it makes me proud. To get translated is an inspiration. When I sit by my desk, and no words come out of my head, when I struggle, I can think: Wow, I have some novels translated into German, this important language which can give me many millions possible readers. Sometimes it helps, the pleasure push me on to fill more pages with stories.

It says at one point in the book “Ich habe den Postmodernismus eigenhändig in Norwegen eingeführt, dachte Alf, als er am Frühstückstisch saß und Lust auf ein Ei hatte…“ (“I have single-handedly introduced postmodernism in Norway, thought Alf, as he sat at the breakfast table and felt like having an egg …”). Did you, Jan Kjaerstad, introduce postmodernism in Norway?

No, I didn’t do that, even if I was the editor of a much read Norwegian magazine called The Window, where we also introduced postmodern thoughts. I have written in more than one essay that postmodernism never came to Norway. If something came, it was a bleak copy, a vulgar version, of what experts called postmodernism. I have also written that I am not a postmodernist. If you should put me in a box, it would be the box of late modernism. My understanding of postmodernism comes through architecture. In my youth I dreamed of being an architect, I drew a lot. On my travels I always look for architecture. In Vienna I have studied the work of for example Hans Hollein. But I don’t write like that. I am a storyteller, but a storyteller that tries to find new ways of telling stories. And if Alf I. Veber, in the novel, is anything, he is an admirer of the Enlightenment. In a new Romantic age as ours, we need the correction from the Enlightenment.

Do you consider your complete works as “eine Anleitung, um einen Streich gegen all das Puritanische, die Reinheitshysterie, die ernsthafte Uniformität“ (a guide against all the Puritan, the hysteria for purity, het serious uniformity) that you see in Norway?

Yes. Very much so. I think that is a national weakness. Not only a weakness, but a danger. It narrows the mind. Henrik Ibsen (now comparison, ha ha) saw that danger, and in his plays he criticised that trait in the Norwegian mentality. I have written an essay called “A tribute to the impure”, where I pay hommage to the fact that the novel was born as a bastard, that is Don Quijote, a parody. I like the trend today of the so called hybrid literature. Novels mix fiction and non-fiction. There are far too many dogmas in Norwegian culture. In a world where migration is a fact, we cannot insist on keeping our flag white and clean.

Did your view on Norway and your life as an author change after the attack on July 22nd 2011?

I will say no. What happened in Norway July 22nd has happened elsewhere in the world for a long time. And it happens every second day in for example Irak (but we don’t react). 22nd of July was a shock for many, and for me – that it suddenly also happened here, in Paradise so to speak. But nothing has changed. Politicians told us in speeches that there should be more empathy, but they forgot their words the day after. There is not much empathy in Norwegian politics, we turn away refugees, also children, in the same way as we did before. Norway has enormous space, and few people, but we don’t want strangers to come and live here. That will be our misfortune in the long run.

Soon, the six and last volume of Knausgard‘s “Min Kamp” will come out in Germany. His work has triggered lots of controversial discussions, especially with Ebba Witt-Brattström. What do you think, how would she react to your portrait of women in the “Kongen av Europa “?

I don’t know. I have a great respect for her. She has done a lot for the consciousness of young women in Scandinavia, and she is a good reader. We need more women and thinkers of her calibre. If she finds something to criticise in my novels, I will lower my head. It is always difficult for a man to write about women, especially when women are minor characters. I have written two novels where women are protagonists. I hope the readers will believe in them. In my last novel (2016), “Slekters gang” (“The Path of Kins”), the women are the storytellers. The novel is based on an essential fact: The most important historical phenomena in the 20th Century is the fight for the women’s equal status, equal opportunity. There is still a lot to do, but compared to the 5000 years before, where women were of less value than men, there has been a great leap forward in the last 100 years. I hope the female novelists will lead the way, write the most challenging fiction, in the 21th Century.

After reading Per Petterson and Knausgard, the German literary criticism recognized a new Norwegian type of author – the suffering man. Do you feel like that is a place where you would fit in, too?

I am not there. I write an other type of novel. My field is the imagination. I try to make our imagination wider. Orlando, Virginia Woolf. What a novel! What a character! For if we don’t make our imagination wider, both in our lives and in our society, we will not survive. There will be no discussion of “the suffering man”, when mankind is wiped out, ha ha. To be honest I hope man will suffer more, our behaviour is disgusting. We should repent. It is time for all women to step forward. Let the men suffer and lick their tears.

In Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84, the male characters are also lonely and searching for spiritualism. Do you think it’s a co-incident that a Norwegian and a Japanese writer of the same generation write about a very similar range of topics? Do you think its maybe even possible to talk about a literacy globalization?

I am open for that view. The world gets smaller. The Internet is there for everybody. But there is no global trend, there are always a myriad of “trends”.

You listed 5 topics for a good book. What do you mean by “Svaghet”?

I mean a novel’s weakness. Critics use to be hard on a novel’s weak spots, but for me the weakness is the necessary consequence of the novel’s strength. Few things are more boring than “perfect” novels. If a writer takes a risk, the novel will have holes, bad passages, illogical gaps in the composition, un-understandable actions, and so on. There are far too many elements of whale in Moby-Dick. But that is the reason why Melville’s novel is so splendid.

In your books, music seems to be very important. What does music mean to you personally?

I am interested in every other art form, because you can find things you can transform into writing. I have always studied painting, photography, movies, television, dance, computer games – and music, both classical and new, and of course popular music. In “The King of Europe” I have especially looked to popular music, the enigma of writing a pop song that all the world sings and hums. For me there is no contradiction to say that a track of an album, let’s say 3 minutes, can give you as much pleasure – and wisdom – as a novel you read for 3 days. Sometimes you can “understand”, with your mind and body, something when you listen to a pop song that you cannot understand even if you read the whole of “The Encyclopaedia Britannica”. Kierkegaard has said something like this: Where the sunshine doesn’t reach, the tunes can reach. I have played classical piano for ten years, and I have played in a rock-band for as many years, so music will always mean a lot for me. I still have my keyboards and guitars.

Who would then be the perfect audience for your book?

Readers who are open minded and curious.

Thank you so much for your time!

Info

Jan Kjaerstad

„Der König von Europa“

Aus dem Norwegischen übersetzt von Alexander Riha

Erscheinungsjahr: 2016, Septime Verlag, 670 Seiten

„Der König von Europa“ kann übrigens portofrei bei Pankebuch bestellt werden!

Foto: SEPTIME VERLAG

Foto: SEPTIME VERLAG

Pingback: Jan Kjærstad: Berge - Besser Nord als nie!